I fell in love with the state of Maine in the summer of 1969 when my dad took us camping to Acadia National Park on Mount Dessert Island. I returned there many times in the following years, sharing the park with friends and family. We’d make the ten or eleven hour drive—two whole days of vacation shot with the length of the round-trip. But the smell of the ocean and the pine trees made it all worthwhile.

Someone told me that Nova Scotia was like Maine on steroids, and ever after I wanted to go there. But the luxury of that much time wasn’t in the cards until after I retired. So it sat on the bucket list until I bought my wee beastie and hit the road for a year-long trip. I planned to spend a few weeks up in the Atlantic Maritimes.

Finally on the ferry!

Nova Scotia did not disappoint.

Peggy’s Cove. This may be the most photographed lighthouse on the Atlantic Coast.

Peggy’s Cove monument to Flight 111

Here’s my campsite in Keji. I gave up having a banquette in my rig. Set it up as a lounging couch. Never knew when I might get the vapors and need to lounge.

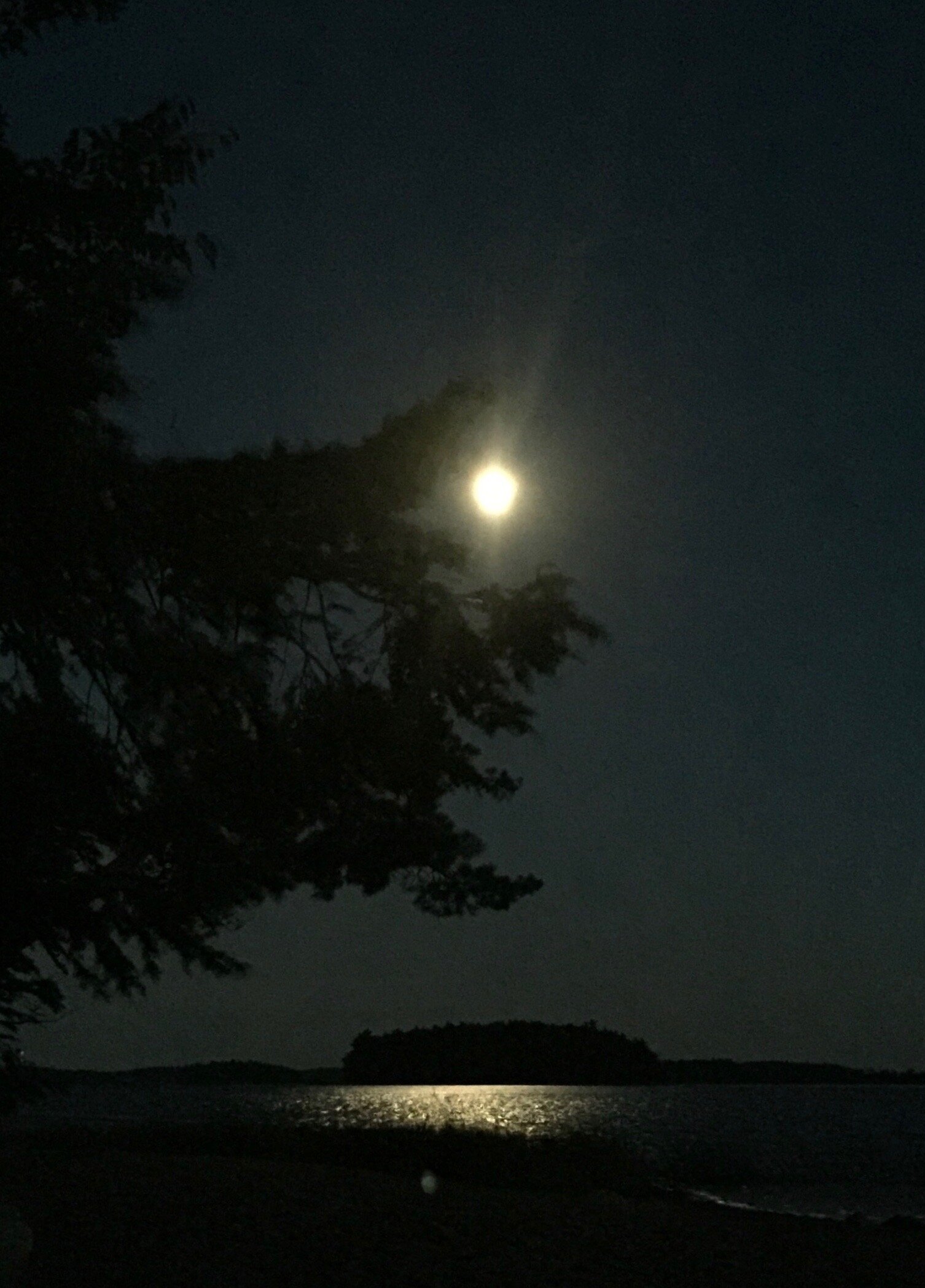

My first night in Keji was the full moon. I saw it rising behind the trees that bordered my campsite. I grabbed the camera and walked back down to the beach to lie down on the warm sand to take photos.

American eagle and American flag.

There are petroglyphs scratched into these spits of land.

Some of these on black background are recreated from the originals

Here’s a Canadian who didn’t take his shoes off very often.

I drove the RV off the ferry and pulled out of everyone’s way to have tea and some breakfast. I had a reservation to stay in Kejimkujik National Park sort of in the center Nova Scotia. I was psyched to stay there. I read that it was a huge gorgeous park, and also a National Historic Site, the ancestral lands of the Mi'kmaw people.

When I arrived, I found that the guidebook actually didn’t do the park justice. It was the most heavily wooded, beautiful campsite I’d ever been in. There was a path out back leading down to a crystal-clear lake. I chocked the wheels and leapt into my swim togs to have swim before dark. After dinner, I noticed a giant full moon rising behind the pine trees which rimed my campsite, so I grabbed the camera and went down to the lake again to take some photographs.

At 2:30 in the morning, I was awakened by an owl. The sound was so unusual to my city-girl ears, and so repetitive, when I first awoke in my confusion, I thought it was coyotes howling at the moon, but the sound wasn’t the “yip, yip, yip,” of a coyote. It was an owl. It was so loud, I thought it must be a very large owl—or perhaps it was very close to my window? A deep, whirring. Repetitive and rhythmic. “Wuhh, wuhh, whhhu, hootowl! Wuhh, wuhh, whhhu, hootowl!” Amazing. I loved sleeping in my motor home. I had a large window right next to the bed, to let in, or keep out the night sounds, and this night I was so glad it was open!

Next day, I went out in search of a hiking map to the petroglyphs that I had read were here, but the ranger advised me that they can only be seen when you join a tour. I asked if there was a tour that day, and there was. I was a little late, but was welcomed into the group. Big dude named Nick was leading the tour. He was a local man, and a member of the tribe pronounced and sometimes written as, “Mi’kmaw,” (aka Mi’kmaq, The Acadian First Nations, or AFN). He told us of a team of archaeologists who had been brought in to sample ten sites, ten random squares, all over this area and the islands. Seven out of the ten yielded many, many artifacts of his ancestors. The deeper the archeologists went, the more they found, and there was strong evidence of evolving forms, which indicated that the same groups of people used these places for a very long time. They were able to trace them back something like eleven-thousand years.

Sadly, the petroglyphs we saw were in amongst more modern graffiti, as the site was unprotected until 1974 when the park was created. Today, it’s protected by the Canadian Government. The images we were able to see were created about six-hundred years ago. They were located out on a spit of slate that had been compressed, and smoothed by the glacier, and eroded over time by the waves, snow, and ice. Much had been erased by these forces over time. There were layers of names, symbols, and images scratched onto these rocks, but some were clearly done by the ancestors of The Aboriginal People.

These were culturally significant images that repeated all over: the eight-pointed star, hands, feet, faces, sailing ships, and the traditional woman’s peaked cap—usually that was drawn larger than the other symbols, to show how important women were in the culture. They were the tribal leaders. In the past I’d read about matriarchal cultures, but had never experienced a living one. Nick told us that if you met a person you didn’t know, you’d ask them who their mom was, who their grandmother was. That was how they kept track of their family groups. What was also very moving for me was the way this day unfolded, serendipitously to be my day of immersion in the Mi’kmaw culture.

After the tour, I went back to the Visitor’s Center to purchase some postcards of Petroglyphs to mail home, and as I was paying for them, I chatted with the woman behind the counter. She asked if I had enjoyed the morning tour, and asked if perhaps I’d also be interested in an afternoon workshop? It was “An Introduction to Mi’kmaw Culture.” I certainly was interested, and had no specific plans to do anything else that day. I signed up.

This tour turned out to be a very small group, just five of us. Cherie, the leader, was a grandmother of her people, a position of social status, not just a family position. Interestingly enough, before I knew she was the leader, we stood around chatting about our children and our grandkids before the rest of the group arrived. It was way cool to be a grandmother among grandmothers. Very different from the youth/beauty/money culture where I live. The workshop was rich and had a number of different elements.

For the last part, Cherie gave us each a small craft kit in a large scallop shell. Each one had four beads and two small circles of deer hide. We each made our brooch, or amulet out of the prepared materials, using leather needles—I never handled one of those before, they are sharp on three sides. When we were mostly done sewing the leather, Cherie came around and stuffed a tiny bit of cedar inside each one for protection. For me, she really stuffed a lot of it in there, and said it would protect me on my journey. I was moved to tears. She was very kind to me, and I didn’t realize how lonely I was feeling until all these emotions overflowed. I made some kind of heart connection with her.

In my world at home, I have deep connection with a handful of friends and family. Out here on the road, I see people, and chat with people, but no one knows me. No one senses if something is going on with me that maybe I need to talk about. This was a very different life I had put myself in for the space of this year.

Afterwards, I went back to my rig to write, I thought about the way in which our culture treats mothering, like housework and grand-mothering, as this vast store of unpaid and mostly un-recognized labor. I am proud of the way I’ve shown up for my little family over the last ten years. Going to work, and then driving to their place to help out, or hang out with Alice and the kids. Making myself available for “babysitting,” Lately it’s more like hanging out with a bit of minor supervision. I have been able to have a relationship with that family in a way that is such a blessing. I remember when Jack and Ted were little, I would show up there at four in the afternoon, and they would shout and scream—lose their minds a little—running around in circles, as though some rock star had arrived! It was so lovely. Ahh, maybe, that’s all the recognition a grandmother really needs.

While looking over my notes and maps the next morning, I was concerned that I was parked. Sitting there in Keji, when there was yet so much to see. I needed to draw a balance between driving by the “sights” and staying put in one place for a few days or a week, to get a feel for it. To be a part of the landscape, not just always traveling over it. I talked it over with Ed on the phone and he said, “This is the trip, this is the time, and you ought to get your money’s worth out of it.” So, I added a few more days to the end of my stay here.

I was still anxious to fit everything in, and there was a huge trip out there ahead of me. I was hung on the cross of wanting to be here now, to be present, and my impulse to race on to the next thing, and then the next. I don’t know how to do this, but I believe Ed’s right. Maybe I will drive up to Gampo Abbey after all. And the oddly named Meat Cove. That’s as far north as the road goes, to the very top of Cape Breton. I think I’d like to stand there and look out over the Atlantic.

After the pavement ended, I had 18 miles of this video game to negotiate in the rig, with all the contents clanging and banging around in the cabinets. But I did make it to Gampo Abbey.

This is a monument (stupa) built to honor the bones of a holy man who was buried at the abby.

The twins had arrived waaaay down in Florida. Nova Scotia, Cape Breton? Check! Nothing left to do now but head south.